Reggie and Me – After the Code

Trying to write today’s piece on the new (and improved?) Blogger engine. I had it foisted upon me a few weeks ago… but was able to revert to the “Legacy Blogger” like the scared little Luddite that I am. Now, “Legacy Blogger” is giving me quite the headache when it comes to doing… well, anything. Opening a new draft? Takes about three minutes. Inserting a picture? At least 30 seconds. It would seem the folks who run this place really want me to use their new gimmick engine. So far… I’m not enjoying it. Adding images is especially awful. Fix this, Blogger.

—

Let’s finally talk about the end of the Comics Code. There were plenty of factors that led to the Code becoming less of an “Authority” on what comics will be sold… and we go into detail during the episode. For the purposes of today’s piece, however, we’ll just look at the last gasps of its relevancy.

Marvel stopped submitting comics to the CCA in 2001, deciding to use their own in-house rating system from that point on. One notable issue Marvel released that year was X-Force #116 (July, 2001) which introduced the concept that would go on to be known as the X-Statix… instead of the usual CCA Stamp, there’s a little note which read: Hey Kids! Look, No Code!

To be completely honest, I probably wouldn’t have even noticed the lack of code if they didn’t draw any attention to it. That’s just how much of a neutered afterthought the Seal was at this point already. This was the Direct Market edition of X-Force #116… so, what about the Newsstand version (because there was one…)? It still didn’t carry the code… but, it did include a Parental Advisory.

Marvel’s in-house Ratings System would sort of resembled the ESRB that we touched on yesterday. It was actually viewed initially as being too similar to the MPAA movie ratings… so much so that the MPAA complained that they were infringing on their trademark! Weird stuff. Anyway, the Marvel Code was as follows:

- ALL-AGES – Self-explanatory

- T (or) A – Appropriate for most Readers (9+)

- T+ – Teens 13+

- PSR: PARENTAL ADVISORY – Older Teens

- MAX: EXPLICIT CONTENT – 18+

Yes, Marvel MAX. The “mature readers” line that launched out the gate with an F-Bomb. Nothing quite says “mature” like that, right? Hey, grown-ups… comics can be so much more than spandex and capes… they can be riddled with F-Words too! This is why we can’t have nice things…

DC Comics would submit (some) books to the Code Authority for an entire decade after Marvel walked! January, 2011 would mark the end of DC’s relationship with the CCA… although, at that point, they only submitted a small handful of titles to begin with. DC, like Marvel, would rely on their own in-house Code to rate their content:

- E – Everybody

- T – Teen

- T+ – Teen Plus

- M – Mature

Archie Comics would announce their submitting to the CCA in January, 2011. Unless I’m conflating news items, I swear the DC and Archie announcements hit the comics news cycle like the same day. Archie would not introduce an in-house rating system, instead “promised to continue to produce family-friendly, entertaining and relevant stories.” Archie Comics President, Mike Pellerito would say: “We have a great deal of respect for what the Comics Code Authority has stood for over the years, but at the end of the day, the final judge of our content is our readership.”

This rendered the CCA a dead organization. The rights to the iconic Code-Seal now belong to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

So… ding-dong, the witch is dead… right?

Well… maybe not entirely. We’ve got some quotes of the day from our old friend, John Byrne.

On January 20, 2011, Byrne would say “The Comics Code forced writers and artists to be clever. And who wants that???”. He goes on to cite a 1985 Comic Convention discussion panel, during which Dick Giordano fielded a question regarding whether or not the CCA “restricted creativity”. Giordano would respond with, “Lee and Kirby and Ditko had produced all their work on Fantastic Four and Amazing Spider-Man under one of the most restrictive periods of the Code.” That’s… ya know, a really good point. I know plenty of people who hold those hold the Lee/Kirby FF and Ditko-era Spidey as among the best of the best.

Byrne would continue, when after being shown a contemporary page of an issue of Superman (T-Rated). The page depicted an “apparent orgy” and plenty of gratuitous Lois Lane butt-shots. He’d say, “In the end there’s no reason for anybody to be naked in comics, movies, or on TV (…) Humphrey Bogart made a lot of adult (in the true sense of the word) movies, in which nobody got naked, and nobody said ‘f***’ or “s***’.”

Did Byrne have a point? Did the restrictions hamper creativity or foment cleverness? Maybe a bit of both… but, I guess it all really depends on your point of view. We, as consumers of entertainment, seem to place a lot of value on what we think we want… and what we think is being kept just out of our reach. Anytime we hear about Editorial Interference on a comic… we have a knee-jerk reaction that we’ve been robbed of some amazing piece of literature… when, in reality… the edited version might’ve ultimately resulted in the better story. It’s just our human nature that we assume the story we didn’t get is automatically better than the one we do.

An anecdote I added to the discussion here, though I can’t remember if it made air… was discussing the shift in The Howard Stern Show from an over-the-air program to satellite. When Howard was over-the-air, he had to be “creatively crude”. The envelope was pushed… and it worked because they had to be clever about it. Once they moved to Sirius Satellite… and the FCC no longer applied, the show (especially at the onset) became overly curse-filled and raunchy (when Howard wasn’t sucking up to whatever celebrity showed up, that is). This was no longer creative… no longer clever. It didn’t feel edgy… because there were no rules. If everything is “edgy”… then, really… nothing is.

Back to comics… without any guidelines or rules, “Mature Readers” lines became redundant… the industry just didn’t need ’em anymore. The mainstream superhero titles became what we would normally view as the Mature Readers line (minus the f-words and nudity). Instead, now the industry needed to launch “All Ages” lines. An issue of Superman, Batman, Avengers, or Uncanny X-Men of the day… those books, that introduced many folks of my vintage to superhero comics, were no longer appropriate for the preteen (and younger) market. I mean, here’s a series of panels from Avengers (vol.3) #71 (November, 2003):

I’m no prude, but… I know how old I was when I started reading superhero comics (including Avengers)… and, I really don’t think I’d want someone that age reading this. This issue got a PSR/Parental Advisory Rating from Marvel’s Internal Code.

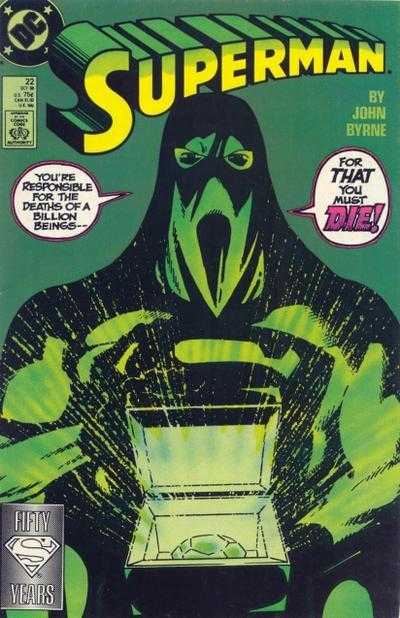

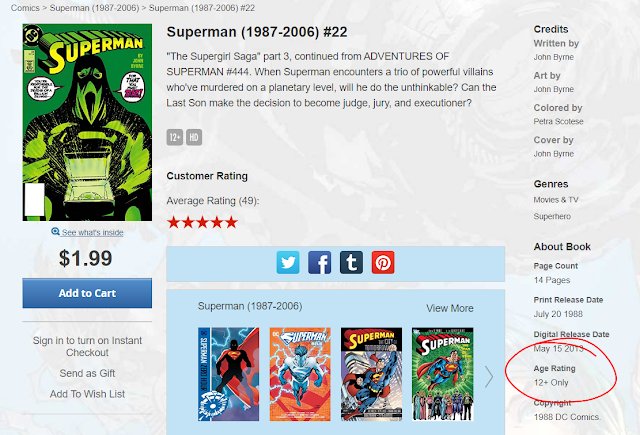

Back to the pre-teen and younger readers. Let’s look at some revisionist coding. An issue I usually go back to when discussing this is Superman (vol.2) #22 (October, 1988). The issue where Superman kills the Phantom Zone Criminals… which, back in the long ago was a CCA-Approved book.

Let’s look at the digital version (made available by DC Comics on May 15, 2013):

12+ Only! A Code-Approved book in 1988… is a 12+ Only book in 2013? Does that imply that this isn’t an “All Ages” book? Was the CCA slapping its seal on just anything? If that was the case… why all the complaints about stifling creativity? I mean, in this issue Superman kills!

We only brought this stuff up as some food for thought. We didn’t have any answers or theories when we recorded this… and, even today, I still don’t. I guess sensibilities change over time… and will continue to. That is something we’ll be discussing further and in greater depth over the next day or two.

Sometimes having a structure to work within produces more creative works, because you need to be creative to work within those limitations.

The thing that always irked me about the code was that it was created when the target audience was 8 to 12 year-olds. As the average age of comic book readers increased the code needed to evolve and understand that who it was designed to protect were no longer the audience reading comics.